I recently read “Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation” by Michael Pollan. You can buy it HERE and a portion of the proceeds will go to the QVF. I recommend that you purchase it, not just because some money will go to the QVF, but because it is beautifully written, enjoyable, interesting, insightful and poignant.

On the surface, Cooked has very little, if anything, to do with fluoroquinolone antibiotic toxicity. Cooked is about the transformation of raw ingredients into food when fire, water, air and earth are applied to those ingredients through the process we call cooking. The section of Cooked that has to do with how things from the earth–bacteria, fungi, etc., are used to transform and “cook” food, is the section I am going to connect to fluoroquinolone antibiotic toxicity.

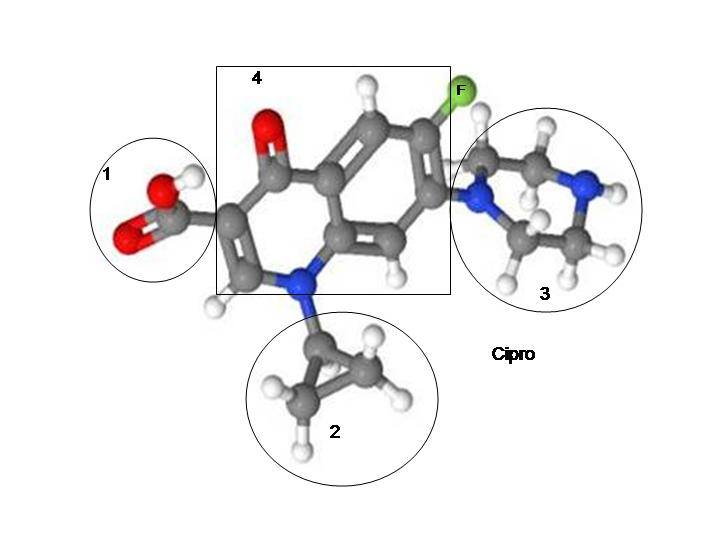

Fluoroquinolone antibiotics are like a nuclear bomb to the gut. They obliterate the microbiome, killing both good and bad bacteria in the gut and throughout the body. They lead to a massive amount of oxidative stress within the gut that further damages the balance of bacteria in the gut. It is only because of lack of knowledge about the importance of the microbiome that Cipro/ciprofloxacin only has a 43 page warning label, not a 100 page warning label. In Cooked, Michael Pollan goes over the importance of the microbiome. He explains the microbiome better than I possibly could, so I’m going to highlight some of my favorite quotes from Cooked in this post.

“Could it be possible that the microbiota also affects mental function and mood, as some of the fermentos I met in Freesone claimed? The idea no longer seems preposterous. A recent study performed in Ireland found that introducing a certain probiotic species found in some fermented foods (Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB-1) to the diet of mice had a measureable effect on their stress levels and mood, altering the levels of certain neurotransmitters in the brain. Precisely how the presence of a certain bacterium in the gut might affect mental function is unclear, yet the researchers found they could block the effect by severing the vagus nerve that links the gut to the brain. Studies like this one make you wonder if it might someday be possible to cultivate, or garden, our microbiota, altering its makeup to improve our physical and possibly also our mental well-being.

Right now, of course, and for the last several decades at least, we have been assiduously doing exactly the opposite: disordering the community of microbes in our bodies without even realizing it, much less with any sense of what might be at stake. Under the pressures of broad-spectrum antibiotics, a Pasteurian regime of ‘good sanitation,’ and a modern diet notably hostile to bacteria, the human microbiota has probably changed more in the last hundred years than in the previous ten thousand, when the shift to agriculture altered our diet and lifestyle. We are only just beginning to recognize the implications of these changes for our health.”

A book that is on my reading list (but that I haven’t yet read) is “Missing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics Is Fueling Our Modern Plagues” by Martin J. Blaser. It’s supposed to be excellent. It is about the diminishing diversity of our microbiota.

Back to Cooked:

“The average child in the developed world has also received between ten and twenty courses of antibiotics before his or her eighteenth birthday, an assault on the microflora the implications of which researchers are just beginning to reckon. Like the pesticides applied to a farm field, antibiotics ‘work,’ at least in the short term. Yet as soon as you widen the lens from a narrow focus on the ‘enemy species,’ you see that such blunt weapons inflict collateral damage to the larger environment, including, in the case of pesticides, the microbial community of the soil. Resistant bugs and various other health problems soon emerge; the soil’s ability to nourish plants and help them withstand disease is also compromised, because the toxins have reduced the community’s biodiversity and thereby compromised its resilience. As in the soil, so in the gut. The drive for control and order ends up leading to more disorder.”

“An interesting question is why the body would enlist bacteria in all these critical functions, rather than evolve its own systems to do this work. One theory is that, because microbes can evolve so much more rapidly than the ‘higher animals,’ they can respond with much greater speed and agility to changes in the environment–to threats as well as opportunities. Exquisitely reactive and fungible, bacteria can swap genes and pieces of DNA among themselves, picking them up and dropping them almost as if they were tools. This capability is especially handy when a new toxin or food source appears in the environment. The microbiota can swiftly find precisely the right gene needed to fight it–or eat it.”

“Taken together, the microflora may function as a kind of sensory organ, bringing the body the latest information from the environment, as well as the new tools needed to deal with it. ‘The bacteria in your gut are continually reading the environment and responding,’ says Joel Kimmons, a nutrition scientist and epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. ‘They’re a molecular mirror of the changing world. And because they can evolve so quickly, they help our bodies respond to changes in our environment.”

Bacteria gene-swap at the drop of a hat. Isn’t that fascinating? It also makes the fact that fluoroquinolones disrupt the process of bacterial DNA and RNA replication quite consequential. I wrote this post about antibiotics altering bacterial DNA back in 2013 – http://www.collective-evolution.com/2013/10/23/genetically-modifying-humans-via-antibiotics-something-you-need-to-know/. The consequences of altering bacterial DNA are still being explored.

Another book of Michael Pollan’s, “The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals” goes over the hazards of applying the industrial model to biological systems–specifically, the folly of using the industrial model to produce food when food production should be a biological, not an industrial, process. The same is true for medicine. The medical system treats people as machines with inputs and outputs and predictable outcomes based on those measured inputs and outputs. It doesn’t work though. Humans are biological systems with feedback and feedforward loops, genetic differences and epigenetic differences, nature and nurture differences, and more–that make conceptualizing humans as machines with predictable outcomes foolish and wrong-headed. When land and animals are used to make food in an industrial, rather than biological, model, unsustainability, externalities and consequences result. When biological systems are respected for the complex systems that they are, sustainability comes naturally. Likewise, when human complexity is ignored and stupid, foolish, one-size-fits-all, industrial medicine prevails, consequences occur in place of health. It turns out that consequences look a whole lot like chronic illness. Whoops.

Lisa’s one-sentence summary of Cooked and The Omnivore’s Dilemma is – Don’t eat processed food. Read the books for a more thorough explanation. They’re both excellent.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here to that Topic: floxiehope.com/the-microbiome-according-to-michael-pollan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: floxiehope.com/the-microbiome-according-to-michael-pollan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: floxiehope.com/the-microbiome-according-to-michael-pollan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on to that Topic: floxiehope.com/the-microbiome-according-to-michael-pollan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: floxiehope.com/the-microbiome-according-to-michael-pollan/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: floxiehope.com/the-microbiome-according-to-michael-pollan/ […]